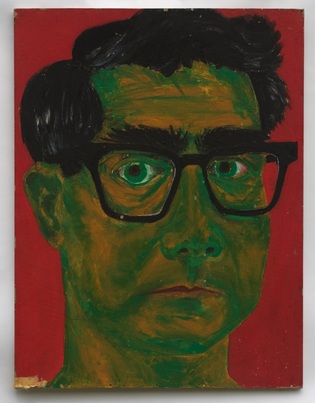

Dorothy Rice, author of The Reluctant Artist Dorothy Rice, author of The Reluctant Artist Dorothy Rice’s memoir and art book, The Reluctant Artist, is a meditation on the author’s relationship with her father, and her efforts to catalog his extensive body of work. The artist, Joe Rice, was dedicated to completing a painting a week, yet despite creating a plethora of striking work, he never showed it or sought recognition for his art. I recently corresponded by email with Dorothy (a good friend from my time at UCR Palm Desert’s MFA program) about writing the memoir, her father’s lasting lessons, and how she came to publish The Reluctant Artist through Shanti Arts. Heather Scott Partington: How did The Reluctant Artist come about? What was its path to publication? Dorothy Rice: The project began with an essay I wrote while taking taking community college classes at American River College. That essay, “The Paintings in the Rafters” told the story of an afternoon when my sisters and I got our father’s permission to haul a dozen or so paintings down from the rafters in his garage, where they had been stored (wrapped and taped up) for over twenty years. The essay was first published in the American River Reviewand then reprinted in the Still Point Arts Quarterly, an arts magazine that I found via the writers’ resource Duotrope. The editor of the Arts Quarterly, Christine Cote, was drawn to the art. She published several full color photos of my father’s work along with the essay and asked if I was interested in working with her on a book about my father and his art. I developed a proposal and we entered into a contract whereby I agreed to deliver text and photographs and she to publish the book. I had no clear idea of what the text would be when I began but it eventually took its present shape, as a memoir touching on the ways in which the artwork affected me as a child, a young adult and throughout my life and, in particular, how my father’s lifelong pursuit of the arts inspired and fed my own creative aspirations. Because my father was always a very reserved man, the artwork had always seemed significant and important to me as manifestations and windows onto an interior life he kept mostly to himself. HSP: Was there anything about the format of the book (art + prose) that presented a unique challenge or opportunity? Can you talk about how the book came together in terms of layout? DR: The layout was primarily the purview of the publisher. She shared sample fonts and approaches to the layout with me, but to a great extent I deferred to her design expertise. When she first began to layout the project she had hoped the photos of the work could be interspersed with the text and placed near to where they are mentioned in the narrative. But she found this too cumbersome and instead opted to put most of the artwork and photos at the back of the book, with only a few images at the beginnings of the sections. We did review several cover designs before arriving at the final. I knew that I wanted the self-portrait I call “The Green Man” on the cover and, for her, that posed some initial difficulties as the image is dark and dominant. We compromised on a smaller photograph that deemphasizes the starkness of the image. I had also wanted to use the title “The Green Man” for the book itself, but arrived at the compromise “The Reluctant Artist” after discussing with her the potential redundancy of the artwork and the title being so closely aligned. What intrigued me the most about the publisher’s approach to the book was that she was wanted a full sense of the artist and his life and was therefore interested in including family photographs and other items of a more personal nature than I would have thought to include in the project without her encouragement. Her publications, at least in my experience, are an unusual blend of art and literature with a strong focus on visual presentation.  HSP: In the book, you say “I tuck things away for safekeeping.” Do your family members have a sense that you remember things better than they do? Or differently? What has your family’s reaction been to the memoir you’ve written about your memories of your dad? DR: I think I have a reputation of “not letting things go,” of holding on to bits of information for later use. In terms of my father and his art, I was probably very irritating at times in terms of keeping track of where everything was and of what had been photographed and what remained to be done. For several years it was a kind of compulsion to gather the complete record and document his art on a website I created as a sort of online archive. Now that the book is done and there is something to show for those years, family members are very supportive and, I think, touched that we now have this unique memento of our father, who, in many ways, was an enigma to us all. As far as memory, I think I have an amazing memory and that I recall many incidents complete with dialogue and other details. Yet I have learned from working on memoir projects these past view years that memory is mutable and that my “truth” isn’t always someone else’s. Our minds all work differently and it has been interesting to hear my sisters’ different takes on the same events. I did have several family members review the manuscript before it was finalized and made a few tweaks in response to their comments, not because I had it “wrong” necessarily, but because different wording could better capture how we all remembered things. For example, as I tend to be more pessimistic by nature than my sisters, my take often reflects that bent. One thing that has been very heartening, and affirming, is that several family members (immediate family, cousins, nieces, uncles) have remarked that I captured Joe Rice, that my portrayal of my father felt true to them. Also, my memories have triggered deeper remembering for them, which was an important reason for putting the book together, to keep his memory alive. Other readers (i.e. non family) have expressed that the portrayal of my father resonated for them because of their own communication issues with a parent, spouse or other loved one. It has invoked the universal difficulty inherent in really knowing another person, particularly when that person is far from transparent. Also the notion of a person quietly pursuing their passion for decades (art in this case) without fanfare and seemingly with no need or interest in any outside approval or acknowledgement has also been a source of inspiration and interest for readers, as it has always been for me. HSP: You write that your father “had a distinct way of speaking”–how do you think his speech, and to some degree, his art–reflect the man that you came to understand him to be? Do you feel like you truly knew him? DR: Interesting question. I always assumed his speech–he would sort of hesitate as if gathering his thoughts and then speak slowly and clearly, enunciating in an almost exaggerated way–had something to do with having come to this country in his early teens from the Philippines. But thinking about it, it could also have simply been that he was a man of few words and he didn’t take them lightly. He always thought before, and while, he spoke. His best art, to me, is careful art–the plotted geometric and surrealistic images of the 60s and 70s, so perhaps there is some concordance there.  HSP: Can you talk about the intersection of your dad’s life with some of the interesting figures in San Francisco in the 60’s? DR: My Dad was an extreme introvert, so his life didn’t intersect with anyone’s in any obvious way. However, he was well read and aware of what was happening in the art world and therefore conversant about artists and art trends. Some of my fondest memories are of visits to museums and galleries and discussions about tastes in art. Like me I suppose, my father was not a joiner, of anything, and he avoided most social events that weren’t mandatory. HSP: What do you wish you could ask your dad now? DR: Related to the question above, I wish I knew more about artists he admired, artists he may have worked alongside or taken classes from at the San Francisco Art Institute, or earlier in undergraduate or graduate school. I always wanted to know what art meant to him, why he did it, why he had no interest in sharing or showing. It honestly puzzled me that as his health began to decline it became clear he hadn’t kept any kind of record of the things he’d created, no notebook or list. I would mention paintings or show him something on my website and he would be surprised, pleased too usually, and say he’d forgotten all about that one. But, to be honest, I realize there’s no use wishing I could ask him things as he probably wouldn’t have answered in any way that I would find satisfactory. I asked lots of things along the lines of my questions above while he was still alive and received monosyllabic responses at best, more often only a wry smile and a wrinkled brow, as if to say, “what’s it to you, nosey pants.” HSP: I know The Reluctant Artist took several forms before it was a memoir and art book. What might readers be surprised to know about those earlier versions? DR: Well, I was always inspired by my father and his art, but I had also always wanted to be a fiction writer. So initially I fictionalized his life and thought it could be some kind of novel. Then, when I began taking writing classes and going to workshops, one instructor suggested I turn my novel into a murder mystery to liven it up. “Throw a dead body onto page two,” was his exact advice. So I did that and spent several years churning out a murder mystery, complete with San Francisco Irish detective, crazed hippies, one victim tossed from the allegedly haunted tower at the San Francisco Art Institute, the other strangled with her pearls in a dank basement. Very noir, very lame, very out of my wheel house. That novel resides in a drawer in my office, well actually, on the floor behind my desk.  HSP: What’s your next project? DR: I am working on a memoir inspired by my experiences as a mother. I never planned to have kids yet I ended up having a child in my 20s, 30s and 40s, one every nine years, plus two stepsons who came into my life with my third marriage. This year, with my youngest child leaving home for college in the fall, I find myself reflecting on the journey, three decades during which I have been many kinds of mother—single, married, step, involved, neglectful and merely misguided. That said, who knows where it will lead. _ The Reluctant Artist is available for purchase here. More information about Joe Rice can be found here. More information about Dorothy Rice can be found here. Photos of Joe Rice’s artwork used with the author’s permission.

1 Comment

Leave a Reply. |

Dorothy, author of GRAY IS THE NEW BLACK, blogs about the challenges and opportunities of being a woman and a writer of a certain age in a youth-centric universe.

categories

All

archives

July 2024

|