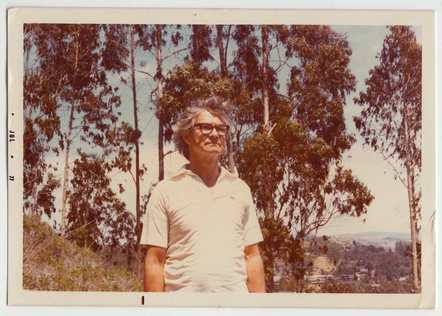

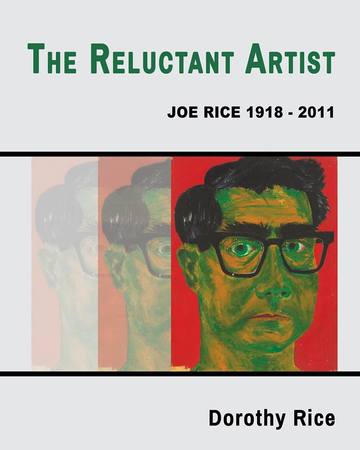

My father, Joe Rice, died seven years ago. If he were still alive, he would turn one hundred this year. It’s a substantial number. A milestone. And a pretty strong indicator that, being his daughter, I’m no spring chicken myself. Dad was an artist and an art teacher. He was also a hard man to know. Not mean, but taciturn and private, a man of few words and fewer outward signs of affection or emotion. As a kid, I assumed he didn’t like me very much, that it was about me. More likely that was just the way he was. In his final years, I struggled to forge an emotional connection with him, before the opportunity was forever lost. Knowing he’d avoid any touchy-feely talk like the plague, I thought art could be the bridge between us. A way to talk about what we both loved without talking about love. “You are a great artist,” I once said, realizing I never had. His first response was to visibly recoil. A turtle receding into its shell. Then, in typical low-key fashion, he said, "It's very kind of you to say that." As if I’d complemented his knit vest or how well the roses he’d planted were coming along. “But you are,” I insisted. “You know that, right?” "I've been a lifelong student of the arts,” he said, with a deep sigh and a nervous glance towards the kitchen, a clear sign that I should change the subject. Humility was a coat he’d always worn. Yet it wasn’t a coat, it was his skin.  On a subsequent visit, I tried a different tack. “You always have something on your easel,” I said. “You’ve done so much.” The walls of the Sonoma home he shared with his second wife were covered floor to ceiling with paintings, a haphazard mish-mash of periods and styles, from nudes to stark geometric hard-edge and surreal imagery. "A painting a week. That’s the goal," he said. At the time, and for years to come, I was disappointed by that answer. I felt short-changed. Just as I had when I was a child, I assumed that what I interpreted as reticence was about me. He didn’t trust me. He didn’t love me. What did I hope for? That he'd reveal the meaning of art, of life itself. Would I have been satisfied if he’d said he painted to quiet the demons in his soul? God only knows. Now that he’s gone, his paintings, ceramics and sketches cover the walls in my home and those of my sisters and our children. His memory remains as vibrant now as when he was alive. Did he ever imagine that he would live on in this way? I’m pretty sure he didn’t make all this with us in mind. Whether or not it was what he wanted, his art remains. It connects us to him. A painting a week. When he first said those words to me, I thought he was being evasive. I see it differently now. Whatever we do – be it baking, gardening, making art, caring for a family – it’s the doing that counts. Not the agonizing over what we think we should be doing but aren’t. Not the myriad ways we find to procrastinate. Not the hand-wringing and excuses afterwards. Not what others think of our accomplishments. A poem a day. A thousand words. Three healthy meals on the table. Love in your heart. A painting a week. He was in his eighties when he imparted that nugget. If I still have such a tangible, measurable goal at that age. If it still brings me joy and satisfaction to put pen to paper, my fingers on the keys, I'm thinking that will be pretty awesome. The doing. That's the pudding. A painting a week. Joe Rice 1918 - 2011.

6 Comments

|

Dorothy, author of GRAY IS THE NEW BLACK, blogs about the challenges and opportunities of being a woman and a writer of a certain age in a youth-centric universe.

categories

All

archives

July 2024

|